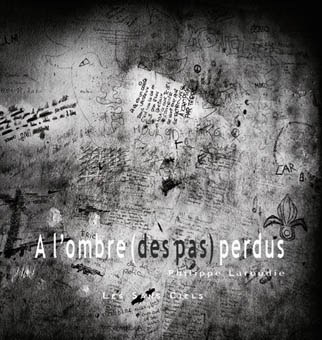

Philippe LAROUDIE

Editeur : Les sans Ciels

Année de parution : 2011

Mais celui qui procède ainsi, qui propose un produit fini ne laissant nulle place à l’interprétation, à la suggestion, prend le risque de rester à la surface des choses, de manquer l’essentiel.

Une autre approche, à l’instar des impressionnistes, est de laisser une part à l’indéfinissable, aux sentiments, au ressenti et, paradoxalement puisqu’il s’agit d’images, à l’invisible, de même que dans un discours les silences utilisés à bon escient peuvent tenir autant de place que les mots.

Il faut savoir gré à Philippe Laroudie de maîtriser cette alchimie par laquelle la vérité, extraordinaire au sens propre du terme, de la prison n’apparaît pas sous la forme de traits définitifs, impératifs, agressifs et simplifiés, mais est traduite, interprétée avec délicatesse, sensibilité et pudeur.

Ici, le rapport aux hommes et aux choses est différent. Les hommes sont des silhouettes, des ombres furtives, écrasées par un décor qui les dépasse et tel objet anodin « à l’extérieur » est lesté d’une considérable charge symbolique, comme ce téléphone, trait d’union hypothétique avec une famille qui vit la prison à sa manière. La lumière n’est pas absente, mais elle perce à travers des barreaux ou des grilles quand elle n’est pas artificielle.

Celui qui nous montre tout cela n’est pas un voyeur indécent, mais un témoin, animé du souci de comprendre et de faire comprendre cet univers dont il semble avoir voulu faire partie pour mieux rendre compte de sa complexité. Et cela, avec humilité : pas de leçon prétentieuse ou moralisatrice dans ces photos, pas de cliché réconfortant pour les bien-pensant rassurés de voirà quoi ils ont échappé, juste des morceaux de vies éclatées, des fragments de souffrance mais aussi d’espérance puisque la vie continue, comme l’exprime cette main que des barreaux n’empêchent pas de se tourner vers le ciel.

C’est ainsi que, de son appareil, le photographe a su tirer bien autre chose que le regard d’un visiteur sur la prison. Il est en quelque sorte l’œil d’un détenu contemplant ses compagnons, mais aussi celui d’un surveillant qui passe lui aussi sa vie en détention. Il ne juge pas, ne compatit pas, il montre et suggère avec discrétion et délicatesse, il exprime. Philippe Laroudie a certainement lu Saint Exupéry qui écrivait que le plus important ne se voit pas avec les yeux mais avec le cœur.Marylise LebranchuA l’ombre (des pas) perdus

In the shadow (of steps) lost

There are many ways of showing reality. Of course, it is always possible to throw a harsh light on a scene, and photography lends itself particularly well to this exercise. It becomes, as it were, anatomic, anthropometric. But if one does this, presenting a finite product which leaves no room for interpretation, for suggestion, there is a danger one might not see below the surface of things and so miss the point.

Another way of approaching reality, just as the impressionists did, is to leave room for the undefinable,

for one’s feelings, one’s emotional perception, and, paradoxically – since what is at stake here is images –

for the invisible. Just as in a speech where silence, when used wisely, may prove to be as important as words.

We must be grateful to Philippe Laroudie for mastering this alchemy by which the truth – literally, the extraordinary truth – of the prison is not revealed through irrevocable, peremptory, aggressive or simplified features but is translated and interpreted with delicacy, sensitivity and decency.

Here, the relationship to men and things is different. The men are mere shapes, fleeting shadows, overwhelmed by a decor they cannot control. And the merest object, perceived as ordinary when “outside”, is loaded with a powerful symbolic dimension, like that telephone, a hypothetical link with relatives who experience prison in their own way. Light is not absent, but it passes through bars or grates, when it is not artificial.

The person who shows us all this is not an indecent voyeur, but a witness, deeply concerned to understand and help others understand this world which, it seems, he has tried to be part of so as to give a more faithful account of its complexity. He has done this humbly: there are no moralizing or pretentious lessons in these photographs, no soothing clichés to please right-thinking people who feel reassured to see what they themselves have not been subjected to. Only fragments of wrecked lives, fragments of suffering but also sparks of hope since life goes on, as we can see from that hand which the bars cannot prevent from turning towards the sky.

And so the photographer, through his camera, has succeeded in transcending the perspective of a mere visitor. In a way, he is the eye of a prisoner observing his companions, but also that of a warder who himself lives his life in prison. He does not pass any judgments, does not sympathize. He shows things and evokes them soberly, subtly, he expresses them. Philippe Laroudie must have read Saint Exupery who wrote that the most important things are not seen with the eye but with the heart.

Marylise Lebranchu

Lettre d’information

75004 Paris – France

+33 (0)1 42 74 26 36

ouverture du mercredi au samedi

de 13h30 à 18h30. Entrée libre

M° Rambuteau – Les Halles

Pour Que l’Esprit Vive

20 rue Lalande

75014 Paris – France

T. 33(0)1 81 80 03 66

www.pqev.org